Onchain Privacy Protocols Need To Be Post-Quantum Secure From Launch

Anything posted onchain today can be viewed, downloaded, and stored by anyone. And blockchains are immutable, meaning there’s no going back and editing information. Luckily, a host of solutions, including Inco, have sprung up to keep this data private.

However, as the information stored on a blockchain is stored forever, the encryption methods that keep the data private need to last forever, too. If the encryption is broken, it doesn’t just mean that transaction data is public going forward, historical data can be decrypted too. So privacy solutions need to hold forever. If they don’t, it won’t matter that your salary information or payment history was encrypted onchain, all of your onchain financial data will be revealed.

This issue has not historically been front-of-mind for many people, because our methods of encryption are very strong and take an impossibly huge amount of compute to break. But that changes in a post-quantum world. Quantum computing means that a host of encryption methods could be broken in the future if they’re not upgraded with post-quantum secure (PQS) schemes, which are not susceptible to quantum decryption.

Therefore, it’s imperative that users, protocols, and institutions choose PQS privacy solutions. If they use a privacy solution that isn’t PQS, they could see all of their data become public in the next few years. Not good.

The Problem: “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” Attacks

Post-quantum security is crucial because the threat model has changed: adversaries can record encrypted transactions, encrypted messages, and encrypted proofs now, store them indefinitely, and wait for quantum computing capabilities to catch up. Even if a protocol is upgraded to become post-quantum secure, transactions downloaded from a ledger without post-quantum secure encryption can still be decrypted.

If the underlying cryptography relies on assumptions broken by quantum computers, then those historical records become plaintext the moment quantum attacks become practical.

Most Current Solutions Are Not Secure

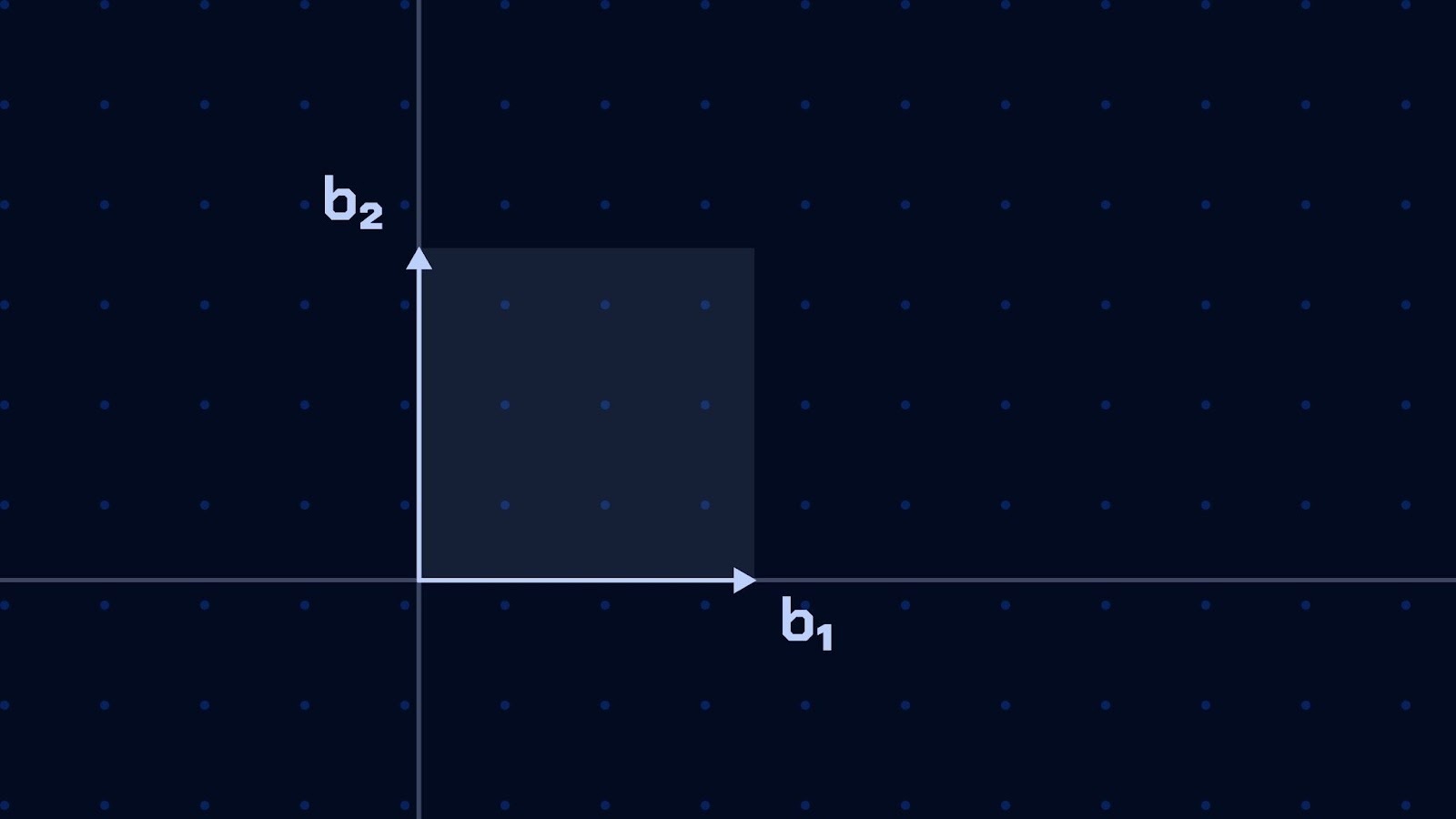

Most privacy protocols, which are based on public-key cryptography setups, rely on some assumptions like hardness of the discrete logarithm problem, or the integer factorization problem. These problems are assumed to be hard, and this makes it possible to build public-key cryptographic systems where it is computationally infeasible to derive the private key from the public key alone.

The discrete logarithm problem does make a lot of sense when it is combined with elliptic curve groups. This combination enables many use cases where there is a need for practically one-way functions. Moreover, traditional elliptic curve-based setups are super efficient in terms of computation and storage cost compared to some alternatives.

Thanks to the hard problems and algebraic structures like elliptic curves, cryptographers have developed many schemes and methods used for protecting existing online activity, such as online banking and browsing through SSL/TLS. Blockchains also rely on the hardness of the discrete logarithm problem, with users relying on it to sign transactions on Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Especially in the current landscape of UTXO-based privacy systems, such as ZCash and Railgun, DLOG-based elliptic curve cryptography is the gold standard for balancing anonymity with performance because UTXO models rely on “blinding” transaction amounts and/or “shielding” identities through zero-knowledge commitments which require cryptographic primitives that are both compact and algebraically flexible. Elliptic curves provide exactly this feature as they enable Pedersen commitments to make a network verify that “inputs equal outputs” without revealing actual values. Moreover, they support keeping the proof sizes small and computational costs low.

Zero-knowledge proof systems such as zkSNARKs are built on the same public-key assumptions. Modern zkSNARK constructions rely heavily on elliptic-curve cryptography — for commitments, polynomial commitments, and pairing-based verification — to guarantee soundness and privacy. While these systems enable efficient, succinct proofs, their security ultimately depends on the hardness of discrete logarithm–based problems. If these assumptions fail, an attacker could forge valid-looking proofs, extract private witnesses, or retroactively break anonymity guarantees for historical onchain transactions. So far, these modes of cryptography have held up.

However, in 1994, American mathematician Peter Shor developed quantum algorithms that were capable of breaking these hard problems. These algorithms require quantum computers, which are currently in a nascent stage of development due to the overhead caused by quantum error correction. But once quantum computers exist that can run these algorithms against current modes of encryption, much of our current technology loses its security. And the “harvest now, decrypt later” approach that hackers are likely to already be using becomes a major worry for anyone who needs privacy on a blockchain.

What Is Post-Quantum Security?

We call a cryptographic protocol “post-quantum secure” if the hardness assumption the protocol relies on is hard enough not to be broken by a quantum computer.

For example, lattice-based setups, which rely on the hardness of the learning-with-errors (LWE) problem, are assumed to be secure against attackers with quantum computers. Most Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) schemes are based on lattice-based cryptography.

STARK proofs are also thought to be post-quantum secure due to their hash-based nature, while most current SNARK proofs are not due to the fact that they are based on the discrete logarithm problem.

It is worth noting here that “post-quantum cryptography” and “quantum cryptography” are separate and distinct fields of cryptography. While post-quantum cryptography focuses on algorithms that are resistant to quantum computers, quantum cryptography focuses on using quantum mechanics to design cryptographic systems.

Why Starting Early Matters

Launching a privacy protocol without post-quantum secure primitives and upgrading it later is not an option, because post-quantum upgrades cannot retroactively protect data that has already been submitted onchain; if someone has downloaded the encrypted record of a blockchain ledger protected through a privacy protocol that is not PQS, they could decrypt it as soon as they have access to a quantum computer. So once encrypted data is exposed onchain, its long-term confidentiality is lost.

We can only protect future privacy by adopting PQS encryption and key-exchange methods before data enters the chain. In the world of immutable ledgers, security is not something you patch later, it’s something you lock in forever.

What This Means

With this in mind, adopting a post-quantum–secure onchain privacy architecture is not optional. Inco uses post-quantum cryptography — specifically X-Wing hybrid KEM — for key encapsulation to encrypt user inputs from the very first interaction with the chain. By relying on a lattice-based key encapsulation mechanism rather than elliptic-curve assumptions, Inco ensures that encrypted data is never exposed to future quantum decryption. This approach protects confidentiality not just at launch, but permanently, preventing today’s private data from becoming tomorrow’s plaintext.

Incoming newsletter

Stay up to date with the latest on FHE and onchain confidentiality.

.svg)